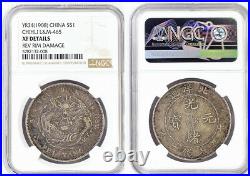

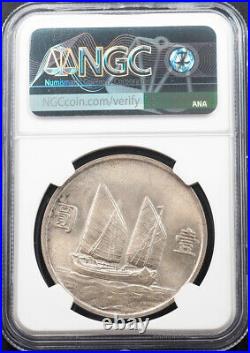

1904, China, Kiangnan Province. Large Silver Dragon Dollar Coin. Mint Year: 1904 Denomination: Dollar Region: Kiangnan Province Reference: L&M-257, KM#Y-145a. Certified and graded by NGC as AU Details: Chopmarked! Obverse: Facing dragon, English legend, sperated by rosettes around. Legend: KIANG NAN PROVINCE 7 MACE AND 2 CANDAREENS. Reverse: Four chinese characters around four mandarin vertical characters, all within circle of pellets. Dots splitting legend at sides! Mint official’s initials (small HAH and CH) at 11 and 2 o’clock! The Guangxu Emperor (14 August 1871-14 November 1908), born Zaitian, was the tenth emperor of the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty, and the ninth Qing emperor to rule over China proper. His reign lasted from 1875 to 1908, but in practice he ruled, under Empress Dowager Cixi’s influence, only from 1889 to 1898. He initiated the Hundred Days’ Reform, but was abruptly stopped when Cixi launched a coup in 1898, after which he was put under house arrest until his death. His reign name means “The Glorious Succession”. Even after he began formal rule, Cixi continued to influence his decisions and actions, despite residing for a period of time at the Imperial Summer Palace (Yiheyuan) which she had ordered Guangxu’s father, the Prince Chun, to construct, with the official intention not to intervene in politics. After taking power, Guangxu was obviously more reform-minded than the conservative-leaning Cixi. He believed that by learning from constitutional monarchies like Japan, China would become more politically and economically powerful. In June 1898, Guangxu began the Hundred Days’ Reform, aimed at a series of sweeping political, legal, and social changes. For a brief time, after the supposed retirement of Empress Dowager Cixi, Emperor Guangxu issued edicts for a massive number of far-reaching modernizing reforms with the help of more progressive Qing mandarins like Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao. Changes ranged from infrastructure to industry and the civil examination system. Guangxu issued decrees allowing the establishment of a modern university in Beijing, the construction of the Lu-Han railway, and a system of budgets similar to that of the west. The initial goal was to make China a modern, constitutional empire, but still within the traditional framework, as with Japan’s Meiji Restoration. The reforms, however, were not only too sudden for a China still under significant neo-Confucian influence and other elements of traditional culture, but also came into conflict with Cixi, who held real power. Many officials, deemed useless and dismissed by Guangxu, were begging Cixi for help. Although Cixi did nothing to stop the Hundred Days’ Reform from taking place, she knew the only way to secure her power base was to stage a military coup. Guangxu was made aware of such a plan, and asked Kang Youwei and his reformist allies to plan his rescue. They decided to use the help of Yuan Shikai, who had a modernized army, albeit only 6,000. Cixi relied on Ronglu’s army in Tianjin. But Yuan Shikai was beginning to show his skill in politics. The day before the staged coup was supposed to take place, Yuan chose his best political route and revealed all the plans to Ronglu, exposing the Emperor’s plans. This raised Cixi’s trust in Yuan, who thereby became a lifetime enemy of Guangxu. In September 1898, Ronglu’s troops took all positions surrounding the Forbidden City, and surrounded the Emperor when he was about to perform rituals. Guangxu was then taken to Ocean Terrace, a small palace on an island in the middle of a lake linked to the rest of the Forbidden City with only a controlled causeway. Cixi followed with an edict dictating Guangxu’s total disgrace and “not being fit to be Emperor”. Guangxu’s reign had effectively come to an end. For his house arrest, even court eunuchs were chosen to strategically serve the purpose of confining him. There was also a crisis involving Guangxu’s removal and abdication and the installment of a new Emperor. Although Empress Dowager Cixi never forced Emperor Guangxu to abdicate, and his era had in name continued until 1908, Emperor Guangxu lost all honours, respect, power, and privileges given to the Emperor other than its name. Most of his supporters were exiled, and some, including Tan Sitong, were executed in public by Empress Dowager Cixi. Kang Youwei continued to work for a more progressive Qing Empire while in exile, remaining loyal to the Guangxu Emperor and hoping to eventually restore him to power. Western governments, too, were in favour of the Guangxu Emperor as the only power figure in China, failing to recognize Empress Dowager Cixi. A joint official document issued by western governments stated that only the name “Guangxu” was to be recognized as the legal authoritative figure, over all others. Empress Dowager Cixi was angered by the move. There was dispute, for a period of time, over whether the Guangxu Emperor should continue to reign, even if only in name, as Emperor, or simply be removed altogether. Most court officials seemed to agree with the latter choice, but loyal Manchus such as Ronglu pleaded otherwise. Pujun, son of the conservative Prince Duan, was designated as his heir presumptive. In 1900, the Eight-Nation Alliance of Western powers and Japan entered China and on 14 August occupied Beijing following a Chinese declaration of war which the Guangxu Emperor opposed, but had no power to stop. Emperor Guangxu fled with Empress Dowager Cixi to Xi’an, dressed in civilian outfits. Returning to the Forbidden City after the withdrawal of the western powers, Emperor Guangxu was known to have spent the next few years working in his isolated palace with watches and clocks, which had been a childhood fascination, some say in an effort to pass the time until the death of the Empress Dowager Cixi. He still had supporters, whether inside China or in exile, who wished to return him to real power. Guangxu died on 14 November 1908, a day before Empress Dowager Cixi. He died relatively young, at the age of 37. For a long time there were several theories about Guangxu’s death, none of which were completely accepted by historians. Most were inclined to maintain that Guangxu was poisoned by Cixi (herself very ill) because she was afraid of Guangxu reversing her policies after her death, and wanted to prevent this from happening. The fact that the two died a day apart is significant. Another possibility is that Guangxu was poisoned by Yuan Shikai, who knew that if Guangxu were to ever come to power again, Yuan Shikai would likely be executed for treason. There are no reliable sources to prove either theory, but the second one has a certain amount of circumstantial evidence to it, because Li Lianying was murdered, possibly by Yuan, after Guangxu died. Official court documents and doctors’ records from the time suggested that Guangxu did die from natural causes. The Emperor had long been sick anyhow, and the records indicate that the Emperor’s condition began to worsen several days before his death. But the illness could have been caused by poison, administered in small doses over a long period of time. On 4 November 2008, forensic tests revealed that the level of arsenic in the Emperor’s remains was 2,000 times higher than that of ordinary people. Quoted a historian, Dai Yi, who speculated that Cixi may have known of her imminent death and may have worried that Guangxu would continue his reforms after her death. In any event, Guangxu was succeeded by Empress Dowager Cixi’s handpicked heir, his nephew Puyi, who took on the era name. Guangxu’s consort, who became the Empress Dowager Longyu, signed the abdication decree as regent in 1912, ending two thousand years of imperial rule in China. Empress Dowager Longyu died, childless, in 1913. After the revolution of 1911, the new Republic of China funded the construction of Guangxu’s mausoleum in the Western Qing Tombs. The tomb was robbed during the Chinese civil war and the underground palace (burial chamber) is now open to the public. The item “1904, China, Kiangnan Province. Large Silver Dragon Dollar Coin. L&M-257 NGC AU+” is in sale since Thursday, January 28, 2021. This item is in the category “Coins & Paper Money\Coins\ World\Asia\China\Empire (up to 1948)”. The seller is “coinworldtv” and is located in Wien. This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Country/Region of Manufacture: China

- Certification: NGC

- Year: 1904

- Composition: Silver

- Denomination: Dollar

- KM Number: 45a.12